COLONIAL GUILFORD

Guilford’s settlers arrived under the Puritan leadership of the Reverend Henry Whitfield. These early colonists were often educated and possessed some means. Most were farmers, but among them were lawyers and skilled tradesmen. Most were fairly young—at 48, Whitfield was among the oldest. Many came from Kent, including Whitfield, his wife, and at least two of her siblings. Others had followed Whitfield from his preaching in Surrey and Sussex. In recognition of their mutual dependence, they committed to each other and to their future in a shipboard covenant.

From the beginning, Guilford’s settlers kept close association with their Puritan brethren in New Haven. That community’s governmental, religious, and educational influence would remain strong throughout the colonial era. Guilford was settled just 15 miles to the east along the coast. A significant number of Guilford’s ministers and teachers were educated in New Haven’s Yale University, whose roots lie in the 1640s. In 1643, Guilford and New Haven combined to form the New Haven Colony, a civil union marked by a shared militia and articles of confederation. In 1662, that colony was subsumed under the Connecticut Colony, in part due to King Charles II’s displeasure concerning the hiding of two judges, “regicides,” in his father’s trial and execution.

Initially, Guilford was known as the Plantation of Menunkatuck, named for the band of Indigenous people from whom they bought their land. The Menunkatuck helped quarry stone for Whitfield’s house, which served as residence, fortress, and community gathering place. Trade in Menunkatuck baskets and brooms was recorded in early town records, as was the hiring of some Indigenous people as servants. According to Bernard Steiner’s comprehensive history of early Guilford, the settlers accorded the indigenous population with respect. However, settlers also feared various Indigenous peoples groups in the region, and for decades they set a watch against attack each night and during religious services.

Civic and religious life were inseparable for much of the colonial period. Ministers and the pillars of the church led the community, which replicated the traditional English social order. Planters, or landed citizens with all civic rights, were at the top of the order, followed by freemen, who had earned civic rights after a probationary period, and common people who had not yet earned their rights. Community officials levied taxes to pay for church and clergy, education, and infrastructure such as bridges and mills. All men were expected to serve the community and colony in a wide variety of public offices, from governor to hayward (the official in charge of fences and livestock enclosures). Women had few rights of their own, but contributed to society as they believed God had ordained—as wives, mothers, and church-members, their work focused on hearth and farm.

The English legal system prevailed, overseen by a general court that met regularly. Records provide a glimpse of daily life—issues concerning property boundaries, wayward livestock, occasional slander, and slight of religious and civic obligations. Well into its second century, little criminal activity was present in the orderly community.

Guilford was dealt a major blow in the late 1640s and early 1650s, when several prominent men died and still others returned to England during the Commonwealth era. The Rev. Whitfield left his flock to return to England during that era of expanded freedoms. Records and letters indicate the community’s fragility and despair following his departure. Guilford survived, due in part to the commitment of the Rev. John Higginson, who previously had taught school and assisted Whitfield, and William Leete, who for over 40 years led his people as magistrate, Deputy Governor, and Governor.

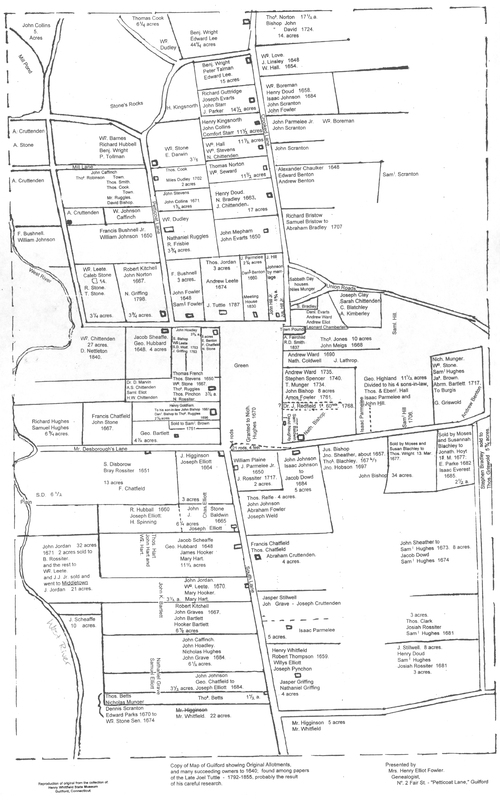

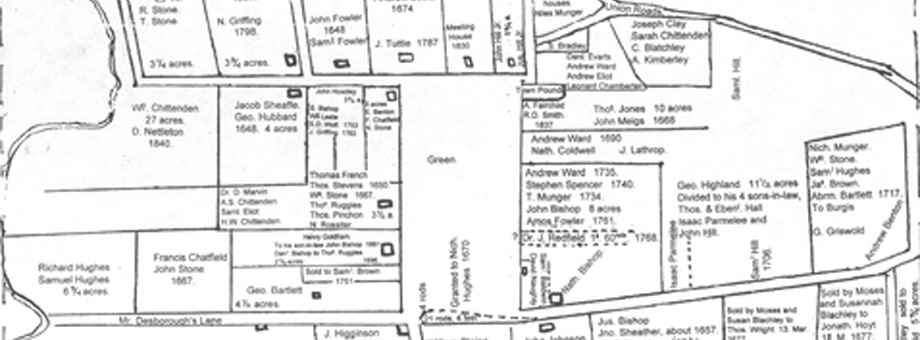

The original settlers were granted land—both house lots and “out lots” of uplands and meadow. The house lots, the core of settlement, were first structured near the Guilford Green. Guilford was a farming community from its earliest days. Agriculture and timbering on the out lots expanded the community’s reach, taming the wilderness according to a divine plan that turned it into a productive, civilized landscape. Policy supported this expansion. Well into the 1700s, Guilford made divisions of land to entice settlement of the seemingly endless North American continent, and rewards were granted for killing wolves, wildcats, foxes, and even woodchucks. East Guilford, later called Madison, was one of the first areas settled outside of the town, beginning as early as 1649.

Although settlement was encouraged beyond the town, Guilford sought to maintain religious and civic dominance over the expanded areas. It was not until 1704 that Madison could boast its own meeting house and all control of taxes. North Guilford achieved this in 1723, and North Bristol (North Madison) in the 1750s. By 1756, the combined population of Guilford and these outlying areas was more than 2,300 people, including 59 people of African descent. A quarter century later, Guilford’s population was nearing 3,000.

Men served in the militia throughout the colonial era, and Guilford had weapons for its defense, but war did not visit Guilford from the 1637 death of a Pequot chief at Sachem’s Head to the American Revolution 140 years later. Many Guilford men fought in various campaigns in the Revolution, Long Island Sound saw goods smuggled through British blockades, and in June of 1781, a skirmish just west of town claimed the life of two Guilford men. Although not all residents supported the Revolution, the majority did. Sanctioning the fledgling American government, town records spoke of liberty being a privilege and a birthright for which their fathers left England.

And so the colonial era in Guilford ended as it began, with a brave community declaring its ideals of freedom and determining to live by them. Guilford’s colonial history traces the very roots of American history, and its legacy is the liberty our society still holds dear.