Lawn & Garden supplies, plants, houseplants. Gifts, bag & bulk mulches.

Hours of operation: All day, everyday (Seasonally Adjusted)

2392 Boston Post Rd suite 2, Guilford, CT, USA

1200 Boston Post Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

300 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Killingworth, CT, USA

842 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

The WAVE @ Sound Life Connections Inc., Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Guilford, CT, USA

1100 Village Walk, Guilford, CT 06437

61 Whitfield Street, Guilford CT 06437

18B Church St, Guilford CT 06437

Tech Fix LLC, 17 Water Street Unit 4, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Mr.J Asian Bistro, 100 Village Walk, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Choice Pet - Guilford, 1059 Boston Post Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Som Siam Thai Restaurant Guilford, 63R Whitfield St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

63 Whitfield St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

14 Water St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

65 Whitfield St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

2311 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

260 River St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

2311 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

2311 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

934 Boston Post Rd, Guilford, CT, USA

1919 Boston Post Road unit 210, Guilford, CT, USA

688 Boston Post Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

35 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Echo Salon, 23 Water St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Swish, 57 Whitfield St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Paperscape Artworks, 20 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

JAIPORE Xpress, 33 Water St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Flutterby, 55 Whitfield St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Ella, where she shops, 90 Broad Street, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Cilantro Specialty Foods, 85 Whitfield St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

77 Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT, USA

2351 Boston Post Rd unit 403, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

1016 Boston Post Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

The Brownstone House Family Restaurant, 961 Boston Post Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

942 Boston Post Rd. Guilford, CT 06437 United States

901 Boston Post Rd. Guilford, CT 06037 United States

96 Fair Street, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

2362 Boston Post RD Guilford CT 06437

514 Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Massage Savvy, Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

1919 Boston Post Road unit 206, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

23 Water Street, Guilford, CT, USA

1063 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

111 Lovers Lane, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

2351 Durham Road, Guilford, CT, USA

1355 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

966 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

725 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

Chapter One Food and Drink Guilford, 25 Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

336 N River St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Nut Plains Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Guilford, CT 06437, USA

140 River St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

21 Shell Beach Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Whitfield St, Guilford, CT, USA

Broad St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Chaffinch Island Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

140 Seaside Ave, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

405 Great Hill Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

9 Indian Meadows Dr, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

181 Ledge Hill Road, Guilford, CT, USA

730 County Road, Guilford, CT, USA

171 3 Mile Course, Guilford, CT, USA

31 Park St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

2351 Durham Road, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

355 Boston St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

32 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

20c Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

71 Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT, USA

81 Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Guilford, CT, USA

411 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Guilford, CT, USA

Guilford, CT, USA

Connecticut 80, Guilford, CT, USA

Tanner Marsh Road, Guilford, CT, USA

West Street, Guilford, CT, USA

3 Mile Course, Guilford, CT, USA

Meadowlands, Guilford, CT, USA

Broad Hill Circle, Guilford, CT, USA

Chittenden Park, Seaside Avenue, Guilford, CT, USA

Laurel Hollow Rd, Guilford, CT, USA

Mulberry Point Road, Guilford, CT, USA

Pent Road, Guilford, CT, USA

Rockland Road, Guilford, CT, USA

525-635 Podunk Road, Guilford, CT, USA

157 E Gate Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

273 Podunk Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

2351 Durham Rd, Guilford, CT, USA

127 Seaside Ave, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

4851 Durham Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

Connecticut 77, Guilford, CT, USA

1390 Durham Road, Guilford, CT, USA

Granite Road, Guilford, CT, USA

32 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Guilford Town Green, Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT, USA

84 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Guilford, CT, USA

30 Boston Street, Guilford, Connecticut, USA

248 Old Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Falkner Island, Connecticut, USA

1 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

248 Old Whitfield St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

171 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Guilford, CT, USA

Guilford, CT, USA

32 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Colonial Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

197 3 Mile Course, Guilford, CT, USA

32 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Fair St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

31 Park St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

60 Tanner Marsh Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

80 Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT, USA

9 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

112 State Street, Guilford, CT, USA

35 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

248 Old Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT, USA

411 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

505a Whitfield Street, Guilford, CT, USA

1355 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

Alderbrook Cemetery, Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

21 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

11 Race Hill Road, Guilford, CT, USA

83 Horseshoe Rd, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

375 Boston St, Guilford, CT 06437, USA

32 Church Street, Guilford, CT, USA

850 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT, USA

15 Boston Street, Guilford, CT, USA

Showing 142 results

Lawn & Garden supplies, plants, houseplants. Gifts, bag & bulk mulches.

Hours of operation: All day, everyday (Seasonally Adjusted)

We are a specialty shop that sells “dirty sodas” which are traditional soda or energy drinks with flavored syrups and creams. We also offer Croffles which are croissant dough cooked in a waffle maker then covered in various toppings. We will be adding Italian Ice to our menu when the weather warms up.

We offer birthday parties and private events.

Hours:

Saturday 10-7

Sunday 11-5

Monday closed Jan/Feb

Tues-Fri 11-5

Spark by Hilton Guilford is a newly renovated hotel conveniently located on Boston Post Road in Guilford, Connecticut. Our family has proudly owned and operated this property since 2003, and in May 2024, we joined the Hilton family under the Spark by Hilton brand. The hotel features 45 modern guest rooms, complimentary breakfast, free Wi-Fi, and a 24/7 market. As a family-run business, we take pride in providing clean, comfortable accommodations and warm, personalized service. Whether traveling for business or leisure, guests can expect a bright, reliable, and welcoming stay near the Connecticut shoreline.

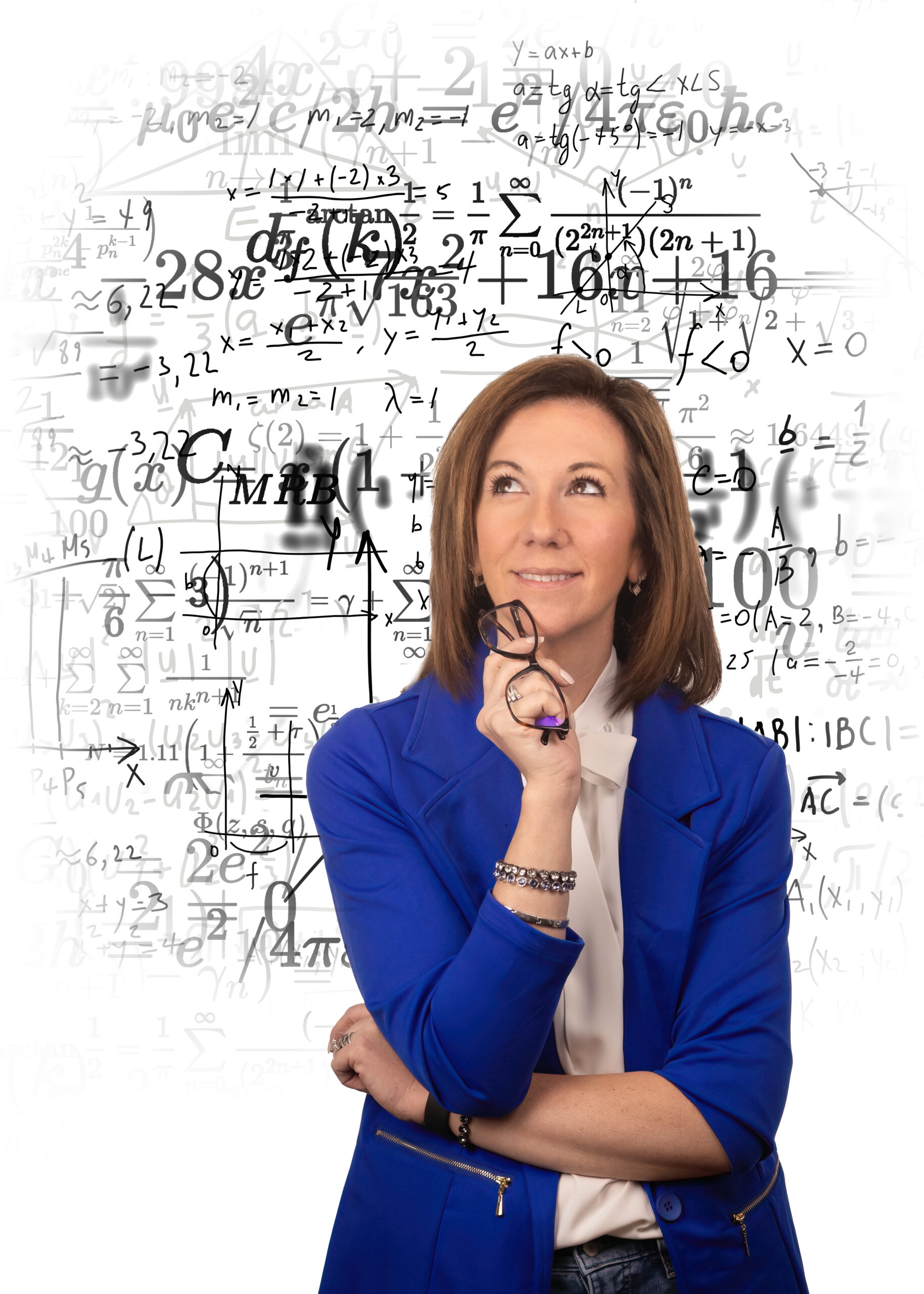

On The Money, LLC is dedicated to delivering professional bookkeeping services that help businesses thrive. With a focus on accuracy, integrity, and financial transparency, they aim to simplify your financial processes and empower you to make informed decisions. Working as part of your team, they are committed to providing top-notch bookkeeping solutions tailored to your unique industry.

Call or Text, 860-452-2242

Truly healthy protein shakes. Fresh hand crafted shakes with high-fiber, protein-rich, low sugar, and all natural ingredients.

Our protein shakes are simple: milk, protein, fruits, veggies, natural nut butters, and minimal added sugar.

No artificial flavors or syrups — ever. We also offer vegan protein shakes and gluten free protein shakes, so everyone can sip happy. Just like homemade… but way better.

Hours of operation:

Mon-Fri 7:00am to 7:00pm;

Sat & Sun 8:00am to 5:00pm

Inclusive cafe employing young adults with disabilities. Offering gelato, espresso and candy.

Join a former Earth Science teacher for a guided kayaking experience that blends

outdoor adventure with a hint of science.

All gear is included: kayaks, paddles,

PFDs, dry bags, and custom field guides tailored to each location.

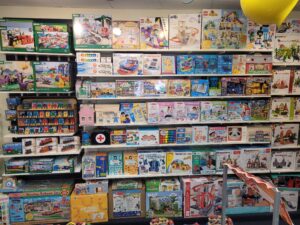

Educational toys, games, crafts, lego, science, baby section, outdoor activities, party favors. A store full of fun!

Hours of Operation:

Monday 10 AM–6 PM

Tuesday 10 AM–6 PM

Wednesday 10 AM–6 PM

Thursday 10 AM–6 PM

Friday 10 AM–6 PM

Saturday 10 AM–5 PM

Sunday 11 AM–4 PM

Jewelry, Repair work, Custom design

Hours of Operation:

Monday, 10 AM – 5 PM

Tuesday, 10 AM – 5 PM

Wednesday, 10 AM – 5 PM

Thursday, 10 AM – 6 PM

Friday, 10 AM – 6 PM

Saturday, 10 AM – 5 PM

Sunday, 11 AM – 4 PM

Alissa blends New York precision with European artistry to create a modern, elevated standard of luxury hair design in New England. Her team is noted for customized looks tailored to each client’s face shape, lifestyle, and elevated hair wellness with some of the best hair products. They are not just hair products; they stimulate hair growth as well as helping with hair loss and any other hair challenges you might face. Let us help you with your hair journey. We look forward to seeing you!

Hours of Operation:

Tues: 9-4

Wed: 10-8

Thurs: 10-6

Fri: 9-5

Sat: 9-3

Rader Helps Guilford with Information Tech, Time, and Talent

Matthew Rader offers the Guilford community his time and talent as a volunteer and an information technology expert.

From serving as a Shoreline Chamber (SC) board member and ambassador to assisting the Guilford Preservation Society’s (GPS) popular Historical Walking Tours to being a Guilford Rotary Club board member, as well as serving the shoreline with his business, Tech Fix LLC, Matthew Rader offers the Guilford community his time and talent as a volunteer and an information technology (IT) expert.

In this digital age, as someone who serves individual and small-business clients with their IT needs, Matthew says that Tech Fix is a busy company.

“The main goal of Tech Fix is to help residential and small business owners in Connecticut, but specifically on the shoreline, with all IT issues,” says Matthew. “It’s helping you work with all your devices and all of your vendors. I like to tell people I’m brand agnostic. I work with all brands, and I’m going to be your IT person to get all of these aggravations working for you and to give you a game plan.”

Matthew’s residential services involve “break-fix” work which attention to incidents and issues ranging from slow Wi-Fi to stubborn printers or broken or nonresponsive devices. For small businesses, he provides monthly services covering all IT needs, such as email, files, computer management, virus protection, phones and internet, and other consulting. The niche for Matthew’s business is serving solo entrepreneurs and small businesses with up to five employees.

“They have one point of contact, which would be me. I help with all their new employees, password resets, all of their IT struggles, on a monthly basis. It’s very popular,” says Matthew.

After working with large corporations, Matthew settled in Guilford in 2010 with a local business, Nerds to Go. He worked with the company for 15 years, including his role as a manager in later years. The company, which was acquired by new owner, abruptly closed in June 2024.

“When it was very abruptly closed, it shuttered the entire IT infrastructure for many businesses that we were working with on a monthly basis,” says Matthew. “Everything was set for deletion. Basically, they would be removed from the internet at the end of June.”

Through his own due diligence, Matthew was able to save those shoreline companies which had recurring volume with the company. From there, Tech Fix was born.

“That’s how I started Tech Fix—to save these companies and to create a company that is very community focused,” says Matthew.

Tech Fix LLC is located at 17 Water Street, Unit 4, in Guilford. To connect with Matthew Rader or learn more, visit www.techfixct.com, email mrader@techfixct.com, or call 203-343-2299.

Hours of Operation:

Monday – Thursday 8:00am-8:00pm

Friday – Saturday 8:00am-9:00pm

Sunday 9:00am-96c00pm

Fine Thai Cuisine in Guilford, CT

Welcome to Som Siam Thai Cuisine, Guilford, CT. Chefs prepare Thai dishes using only the fresh and best ingredients. By using everything Thai, and with the chefs who are master of their profession, the essentially simple and honest nature of Thai food is fully revealed. In terms of service, you will find only a nice smile and prompt delivery of orders here. Another factor that Som Siam always emphasizes is our restaurant’s decoration and atmosphere.

Hours of Operation:

Monday 4:30pm-9:30pm

Tuesday – Sunday 12:00pm-9:00pm

Casual Fine Food

South Lane Bistro is open seven days a week

Dining can be reserved for any group by calling us at 203.533.5845

Indoor, bar, covered porch, and Outdoor Al Fresco garden (seasonal) dining is available

Take out is also available

The full menu is offered, as well as daily specials which are posted on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/southlanebistro/

Hours of Operation:

Monday – Wednesday 4:00pm-8:30pm

Thursday – Saturday 4:00pm-9:00pm

Sunday 4:00pm-9:00pm

Italian Restaurant & Wine Bar

Taste is Our Business

Quattro’s opened in 1996 with one simple philosophy, prepare the best quality cuisine at reasonable prices. Quattro’s specializes in Northern Italian cuisine and a fusion of Italian and Latin flavors. Come enjoy fine dining in a friendly and fun atmosphere. From creative tapas to more traditional fare, Quattro’s will please every member of the family. Eat in or enjoy our extensive take out menu and ask us about catering your next event.

Hours of Operation:

Everyday 11:30am-10pm

Experience the highest quality ingredients, craft cocktails and exceptional service.

Prime on Whitfield has something for everyone.

More than just your traditional steakhouse.

Hours of Operation:

Monday – Saturday 11:30am-10:00pm

Sunday 11:00am-9:00pm

2311 Boston Post Road, Guilford, CT 06437

(203) 643-1540

https://order.toasttab.com/online/mexitaly-kitchen

https://order.toasttab.com/online/mexitaly-kitchen-2

Connecticut’s Healing Salt Cave & Wellness Spa

Private event parties, hydrafacial, cryofacial, microdermabrasion, various facials, massage, cupping, reflexology, shiodara, salt cave, wellness pod, jacuzzi, infrared sauna, and yoga

Hours of Operation:

Tuesday – Saturday 10:00am – 6:00pm

Sunday 10:00am – 4:00pm

Shop Westwoods Wine & Spirits for your favorite wine, beer or spirits.

Hours of Operation:

Monday – Saturday 10:00am – 9:00pm

Sunday 10:00am – 6:00pm

A trendy, ECLECTIC artists boutique with unique choices of handcrafted gifts made by local artists, Nearly every item in the store is handcrafted by over 50 shoreline artisans with a wide variety of goods. There’s something for everyone here!

Prepared meals and desserts. A full service catering store.

Burgers, fries, shakes, hot dogs, veggie burgers, chicken tenders.

Ours of Operation:

11am – 8:30pm

Bo Tique is your go-to for thoughtfully curated gifts, stylish accessories and personalized treasures. We specialize in custom, lasered gifts that tell a story adding a personal touch to create something meaningful, one-of-a-kind gift from the heart.

Hours of Operation:

Monday & Tuesday: Closed

Wednesday through Sunday: 11am – 6pm

Medspa, facials, injections, permanent makeup, massage, makeup by appointment

Hours of Operation:

Tues: 10-5

Wed: 11-7

Thurs: 11-7

Fri: 10-5

Sat: 9-4

.

Stephanie Huffman is a life long Guilford resident and business owner for 25 years. Echo is a unique hair salon located just off the Guilford green.

Echo is a full service hair salon. Specializing in Procell hair loss treatments, Hot heads Hair extensions, KGloss all natural smoothing treatments and all color services.

We are an exclusive Kerastase salon, also carrying R&CO and Awaken products.

Hours of operation:

Tuesday: 10 – 7

Wednesday: 12 – 6

Thursday: 10 – 7

Friday: 10 – 5

Saturday: 10 – 4

First time clients receive a 20% discount when mentioning this page.

Stop by PaperScape Artworks, Guilford’s premiere Papermaking Studio and Art Gallery.

Our unique items make the perfect hostess or anyday gift!

Paper/artwork is handmade from plant fiber such as cotton/abaca, Kozo (from the mulberry plant) and inclusions from nature. Paint is not used in my artwork, just layers of pigmented pulp.

Pickup handmade notecards, and create special memories from wedding and funeral flowers.

Studio Time and workshops are available upon request.

Hours of operation:

The shop is open 7 days 10:30AM – 5:30PM

Flutterby, your stop for retail gifts, including men’s & women’s clothing, in Guilford!

We definitely have something for you! With many handmade and one of a kind items made mostly in the USA

Flutterby’s collection ranges from candles, accessories, pillows, bar ware, baby gifts and body care to super cool clothing!

Owner/buyer Beth OBymachow creates a merchandise assortment that stimulates your senses and keeps everyone coming back for more.

We’re open 7 days a week!

Hours of Operation:

10AM – 6PM, later Summer & Holidays

Ella, where She shops in Guilford, Connecticut, is a must-visit boutique offering a thoughtfully curated selection of stylish women’s clothing in sizes XS through XL.

Whether you are looking for dressy outfits, casual everyday wear, or something that blends comfort and chic, Ella has it all.

The boutique boasts a modern yet inviting atmosphere, with a collection that is both trendy and timeless.

Shoppers love the high-quality pieces, unique accessories, and friendly, knowledgeable staff who help create a personalized shopping experience. Whether you are dressing up for an event or looking for the perfect pair of jeans.

Ella is a go-to destination for fashion in Guilford!

Get ready to shop like never before! Our brand-new, revamped website is here to make your online shopping experience smoother, faster, and downright amazing!

Hours:

Monday-Friday 11AM – 5PM

Saturday 10AM – 5PM

Sunday 12PM – 4PM

Since opening our doors in 2015, The Marketplace at Guilford Food Center has redefined convenience and truly embraces the ‘Your Market. Your Place.’ philosophy. Nothing says local charm quite like The Marketplace. With a rich history and deep community roots, our one-stop shop—café, bakery, deli, grocery, meals-to-go, and catering—will keep you coming back for more. We happily serve the shoreline communities and beyond.

The Marketplace sets the standard for delicious food, quality customer service, and a welcoming casual atmosphere. We offer indoor dining, outdoor patio dining, take-out, online ordering (store orders and catering), in-store events, and local delivery (catering only, DoorDash available for store orders).

Centrality Physical Therapy & Wellness is a physical therapy clinic specializing in pelvic health considerations for pediatrics into adulthood. Conditions that we treat are often “too taboo for the dinner table” and many believe they “just have to live with it.” These conditions can occur at any age and can range from urinary or fecal incontinence, constipation, withholding, bedwetting, urinary urgency or frequency, pediatric daytime accidents of any kind, pain with sex, male or female pelvic pain, pregnancy challenges, birth prep, postpartum recovery & more. Our sessions are 1-on-1 with a doctor of physical therapy for 60+ minutes every session. To learn more about pelvic health physical therapy, our team, or to learn if you could benefit, please contact us directly and we would be happy to support you.

Serving Italian food like family.

At the Guilford Bistro, we have been committed to deliver fresh, simple and delicious dishes since 2006. Our menu is a combination of traditional regional Italian recipes with a modern execution. Whether you are looking for gourmet salads and panini, fresh pasta, fish or steak, the perfect espresso and Italian gelato, we will satisfy your needs.

Visit us in person or order takeout and let us bring our culinary family tradition to you. Catering service available upon request.

The Guilford location of the ice cream voted Best by Connecticut Magazine. Seven days a week, five gallons at a time, we churn fresh cream with generous amounts of pure vanilla, real chocolate and fresh berries to produce the sinfully richest, creamiest ice cream you’ve ever tasted. Locations in Hamden, New Haven, Branford, Madison and Guilford.

The Place Restaurant is a truly unusual restaurant where visitors dine outdoors while a crackling wood fire roasts savory clams, smoky lobsters, sweet corn and much more. Instead of chairs, tree stumps encircle bright red tables, decorated with a bottle of freshly cut flowers. One large menu towers over the dining area, allowing all to see their options as smiling waitstaff come to take their order. Cash only. ATMs nearby. Seasonal: Last weekend in April through October. October is weekends only. Weather permitting. Times may vary throughout the season. Please call for details.

We understand that there are moments in our lives that truly challenge us. For over 30 years, the Women & Family Life Center (W&FLC) has been offering women and all families a strong network of support, education, and community during challenging life transitions such as domestic or sexual violence, divorce, housing insecurity, bereavement, obtaining basic needs, career services, individualized appointments with a volunteer financial consultant or lawyer, and much more. W&FLC Guided Assistance Program (GAP) allows you to meet confidentially with a Referral Navigator. Our team is here to provide personalized support and guidance every step of the way, ensuring that your unique needs are met. Our participants at W&FLC are a part of a supportive community dedicated to your success and well-being. Let us walk alongside you on your journey.

W&FLC serves the towns of Branford, Chester, Clinton, Deep River, Durham, East Haven, Essex, Guilford, Killingworth, Madison, North Branford, North Haven, Old Saybrook, and Westbrook.

W&FLC’s services are open to everyone, without any discrimination based on income, race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin, or disability. We serve the following 14 towns, and all our services are provided at no additional cost to our participants. You are welcome here.

Mission: To support and empower women and all families during challenging life transitions.

Vision: Communities where women and all families are free from violence and harassment, are economically and emotionally secure, and have access to equitable opportunities.

We are a family owned and operated independent auto repair garage. Some things we pride ourselves in are: constant communication and transparency with our clients, catering to their well-being, top-of-the line quality automotive repair, and continuing to innovate in an ever changing field. We offer full-service repair by ASE certified technicians that are on hand at all times. We offer pick up and delivery, and loaner cars to all customers. So, if you have any car care needs or would like to come see what we’re about, give us a call or stop by!

Massage Savvy, a family-owned business, has been dedicated to providing top-quality massage therapy and skin care services since 2011. With over 15 highly skilled massage therapists and estheticians on staff, we offer a wide range of treatments designed to help you look and feel your best. Our team is committed to tailoring each session to meet your specific needs, whether you’re seeking relief from stress, addressing muscle tension, or enhancing your skin’s natural glow.

At Massage Savvy, we believe that self-care shouldn’t be a luxury reserved for special occasions. That’s why we’ve worked hard to make our services affordable, so you can incorporate regular treatments into your lifestyle without breaking the bank. We understand the importance of maintaining your well-being and aim to create an environment where relaxation and rejuvenation are accessible to everyone.

From soothing massages that alleviate stress and pain to personalized skin care treatments that leave your skin refreshed and revitalized, we’re here to support your wellness journey. Our long-standing reputation and commitment to excellence have made Massage Savvy a trusted name in the community. Let us help you take better care of yourself—because you deserve it.

Relax. You deserve a break. Recenter. Immerse yourself in relaxation and tranquility. Renew. Recharged and refocused you can conquer all that the day has in store for you.

Spavia Guilford Commons is all about you – you select treatments that best suit your needs and desires. Our therapists and estheticians care about your well-being and provide each spa treatment in the most personalized, professional manner possible. Begin your relaxation by unwinding in our peaceful S

pavia retreat room. Each guest is provided with a spa robe, spa sandals and a warmed aromatherapy neck pillow for the ultimate rest and relaxation.

Whether you desire a soothing massage or a rejuvenating body wrap, our specialists will assist you in creating the perfect day spa experience. Turn back the clock with a nourishing facial and finish your spa day with an all-natural beauty treatment. You will leave the spa looking – and feeling – your best.

When you are looking for a break from the everyday stresses, we invite you to relax, recenter and renew at Spavia Guilford Commons. Schedule your relaxation today!

Lille Shoppe specializes in thoughtfully sourced goods from beautiful places, located just a short walk from the Guilford Town Green at 23 Water Street, Unit 5. You’ll find unique, high quality goods curated from all over the world for your home and lifestyle. The shop is warm and welcoming – come drop by and say hi! We are open from 10-6, Sunday 10:30-5. Closed Tuesdays.

Abby Mattern founded Lille Shoppe in 2024, combining her passions for travel, design, sourcing, and styling. The items in the shop were carefully selected in Denmark, Sweden, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and England, but extend even beyond these places. The assortment will continue to grow and evolve as new places are traveled to and continue to inspire.

Moonshots located at 1063 Boston Post Rd, Guilford CT website: https://drinkmoonshots.com/

Moonshots located at 1063 Boston Post Rd, Guilford CT website: https://drinkmoonshots.com/

The Farmers Market at the Guilford Fairgrounds is a Thursday destination market located in Guilford, CT. The market is open annually starting in early May and runs until mid-fall (normally will run until the end of October with the possibility of running into November weather dependent). The market is proudly hosted by the Guilford Agricultural Society. Vendors offer fresh and locally grown fruits and vegetables as well as baked goods, artisan breads, meats, seafood, fresh pasta, eggs and many more specialty products. You will also find local, CT made crafts at the market.

VISIT US

Bishop’s Orchards Guilford Farm Market & Winery, 1355 Boston Post Rd. in Guilford is open year round.

Bishop’s Orchards Guilford Pick-Your-Own Orchards are located at multiple fields. Please visit our Pick Your Own page for locations. Our Pick-Your-Own Season runs from June with Strawberries, till the end of October with Pumpkins.

BUSINESS HOURS:

HOLIDAY FARM MARKET & WINERY HOURS

Open 7am-7pm Thanksgiving Eve

Closed Thanksgiving

Close at 4pm Christmas Eve

Closed Christmas Day & Day After (26th)

Close at 5 pm New Years Eve

Closed New Years Day

Closed Easter Sunday

Closed Monday – Memorial Day

Closed 4th of July

FARM MARKET HOURS

Monday – Saturday 8:00 a.m. – 7:00 p.m.

Sunday 9:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m.

WINERY HOURS

Monday – Saturday 8:00 a.m. – 6:30 p.m.

Sunday 10:00 a.m. – 5:30 p.m.

Bishop’s Orchards Northford Farm at 1920 Middletown Ave in Northford is open weekends only (and Monday Columbus Day) from Sat 9/14 to Sunday 10/20 for apple picking, cider, donuts, pies, cookies and apples.

HISTORY

B.W. Bishop & Sons, Inc. is a family-owned and operated farm corporation, doing business as Bishop’s Orchards. The farm was started in 1871 by Walter Goodrich Bishop who engaged in general farming including dairy, vegetables and ice. His son, Burton Walter Bishop, joined him and expanded the business. In 1909, they set out the first commercial orchard. Burton’s sons, Arthur F. and Charles R., joined with their father in 1918 and continued to set out more orchards on land purchased in 1920 and 1926. Generations 3-7, expanded the business by adding a seasonal retail market (at the present location), pick your own fruits and other crops, bakery, winery (including a 25-foot wine bar), and a second location located on Rt. 17 in Northford.

Guilford White House Florist is a full-service florist serving the Town of Guilford for over 75 years. Creating custom floral designs for all of life’s special occasions. With your vision and our knowledge and experience, “Our Flowers Make The Room.” Other services provided are, fruit and gourmet baskets, green and blooming plants, root candles, and fine chocolates from DeBrand. If you are looking for something special we will help you find it at Guilford White House Florist.

Come dine and unwind at KC’s Restaurant and Pub, where you’ll find your favorite comfort foods, a fun kids menu, and the best wings on the shoreline! Relax with our selection of local craft beers and handcrafted cocktails while catching the game on our seven TVs. Come early and enjoy our Happy Hour menu and daily specials. Whether you choose to sit in the dining room, at the bar, or on our patio, KC’s becomes your favorite gathering place for good times with family and friends.

Chapter One Food & Drink offers something for everyone!

With a large outdoor, dog friendly patio and lawn, as well as a cozy dining room and bar we can accommodate parties of all sizes.

Our menu offers everything from fresh seafood and salads to burgers and steaks.

Additionally, Chapter One has a weekday Happy Hour from 3:00pm to 6:00pm.

Stop by for an intimate date night or a fun dinner with friends. You won’t be disappointed.

Hours of Operation:

Monday – Friday 11:30am-10:00pm

Saturday & Sunday 10:00am-10:00pm

Welcome to Chaffinch Island, a tranquil haven nestled at the end of Chaffinch Island Road. This breathtaking 22-acre park is the perfect destination for those seeking a serene escape, a family picnic, or an unforgettable day of fishing. Whether you’re a local or visiting, Chaffinch Island offers a picturesque backdrop to unwind and reconnect with nature.

Chaffinch Island is more than just a park—it’s a slice of paradise waiting to be discovered. Whether you’re planning an afternoon outing with friends, a cozy family gathering, or simply looking for a quiet retreat, Chaffinch Island has something for everyone. With stunning views, fresh breezes, and plenty of amenities, it’s no wonder people keep coming back.

You’ll find Chaffinch Island conveniently located at the end of Chaffinch Island Road. Don’t forget your picnic basket and fishing gear for a perfect day out!

Capture your moments and make memories at Chaffinch Island—your next adventure awaits!

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: Priscilla Otte Preserve

Photo credit: Guilford Conservation Land Trust

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: Munger Brook

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: Meeting House Hill Preserve

Photo credit: Guilford Conservation Land Trust

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: County Road Fields

Photo credit: Guilford Conservation Land Trust

To collect, preserve and share the history of Guilford, Connecticut for present and future generations.

203-453-2236

Welcome to the Historic Guilford presentation of Homes of

Civil War Soldiers.

The 10-mile loop, taking approximately 45 minutes, will pass by over 50

locations where soldiers resided before and after the war.

21 Whitfield Street

William Todd Seward lived here in 1860.

William was commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant in the 1st CT Light Artillery

and then commissioned as Captain in the 7th CT Infantry. He later served

in the US Volunteers Commissary Department until July 1865, serving

almost 4 years total.

15 Whitfield Street

Abraham B. Fowler lived at 15 Whitfield Street. He was a moulder, and

his father George was an apothecary who owned a drugstore at #17

Whitfield Street. Abraham served in the 1st CT Light Artillery for almost

two years.

86 Water Street

John Norton, built this house. John, a blacksmith in town, married

Lucinda Leete and had 3 children. He moved to Middletown, CT where

he was a respected member of that community prior to enlisting in

Co. I, 21st Regiment, CT Infantry.

During the long and weary march to Falmouth, Virginia, which began on

October 28, 1862, the men were exposed to the elements without shelter.

Many of them became sick with typhoid fever, John Norton one of them.

He died on Christmas day 1862 at the Regimental Hospital in Falmouth,

Virginia.

39 Boston Street

Samuel B. Dunn lived at 39 Boston Street with his parents and his

great uncle, Zenas Bradley, who owned the home. Samuel was a joiner, a

carpenter who joins pieces of wood without the use of nails. He married

and moved to Derby, CT prior to enlisting as a Corporal in Co. K, 13th

Regiment, Connecticut Infantry.

The regiment, raised under the name “The Knowlton Rifles” became

known as a fighting company, rarely missing an opportunity to distinguish

itself. The regiment fought mostly in Louisiana where Dunn was promoted

twice. On September 19, 1864, the army was on the Winchester, Virginia

side of the Opequon Creek (Virginia) and engaged the Rebels.

Dunn, the brave and faithful First sergeant was struck, his hands torn by

grapeshot. He held up his mangled hands and Major Homer B. Sprague

threw a cord around them to form a compress. Badly wounded Sergeant

Dunn was taken to Jarvis, USA military hospital, Baltimore, Maryland,

where he received treatment for his wounds. He died a couple of weeks

later from bacteria in the bloodstream.

Boston Street

Boston Street can claim to be one of the most patriotic streets in town,

sending a high number of its residents to fight for the Union.

One family that lived on Boston Street was the Fowler family. Samuel

Fowler and 3 of his sons served. His oldest son, Thomas, enlisted at the

beginning of the war and fought at the first Battle of Bull Run. Since the war

was thought to only last 90 days, this regiment was in service for only 3

months. Thomas reenlisted in Co. A, 10th CT Infantry and was promoted.

Another son, Wallace, who was only sixteen at the time, enlisted in

Company B, 16th CT Infantry. He was captured in battle at Plymouth, North

Carolina and sent to Andersonville Prison. He survived.

A third son, Emerson, was only 14 at the time, and too young to enlist.

Instead, he served as an officers’ waiter in the 27th Regiment, the same

as his father.

Samuel, the father, was wounded in the knee at the Battle of

Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862 and sent to the College General

Hospital in Georgetown. While the father was receiving care for his wound,

Emerson, the youngest, took sick and died from Typhoid Fever on

Christmas Day 1862. Samuel, the father, died just 15 days later from his

wounds. Others who lived on Boston Street included Richard L. Hull who

was killed at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862 and John R.

Burgiss who died from malignant fever while at Shrewsbury, Louisiana.

60 Boston Post Road

The next house is near the Guilford/Madison town line. Lewis Blatchley

lived at 60 Boston Post Road. He enlisted in Co. G, 15th CT Infantry and

was killed in action at the Battle of Wyse Forks in Kinston, North Carolina

on March 8, 1865.

The Battle of Wyse Forks, also known as Second Kinston, occurred

between March 7 and 10, 1865. The highest number of casualties for

Guilford during any single engagement occurred on March 8, 1865, when,

while briskly engaged, the regiment was enveloped by a division of the

enemy who had gained their rear. Two Guilford soldiers were killed and

eleven were captured.

34 East River Road

The Grosvenor family from England lived in this home. Three brothers

served for Guilford, two of whom we can verify lived in the house. The

other, Joseph, lived at 48 State Street. The two brothers who lived here

were Daniel and Samuel. Daniel was one of several Guilford men to enlist

as a musician in the 1st Regiment, New York Volunteers Band. He was

discharged and later became a blacksmith living at 17 East River Road.

Samuel, the third brother was wounded at the Battle of Antietam in 1862,

captured at the battle at Plymouth, North Carolina in 1864, sent to

Andersonville Prison in Georgia and then Florence Prison in South

Carolina where he suffered even more severely. After 232 days of

imprisonment, he was paroled. He was granted a furlough and was able to

spend Christmas 1864 with his family who had by then moved to 384

Clapboard Hill Road.

After his furlough he returned to service. This unlucky fellow was aboard

the Black Diamond, a picket barge, when the Massachusetts, a Union

steamer, collided with it on the Potomac River just off Blackstone Island,

Maryland, on April 25, 1865 at 12:30 a.m. The Black Diamond sunk in 3

minutes and Grosvenor drowned. T.M. Jacobs, who is on the Guilford

Green today, used the 1864 diary of Samuel Grosvenor to write a book

entitled Almost Home, which is available for sale.

58 East River Road

Two soldiers who died and are listed on the Soldiers’ Monument lived at

58 East River Road. Oliver Evarts lived here in 1850 with the family of

Raphael Ward Benton. Both of them enlisted in Company I, 14th Regiment,

CT Infantry.

Raphael Ward Benton, Ward as he was called, was wounded in the neck

at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. In the days following the

battle Ward suffered in a field hospital, eventually walking over 20 miles

with other wounded soldiers seeking help. At the hospital in Frederick,

Maryland, eight days after the battle, he died due to blood loss, fatigue,

and improper care. His body was returned to Guilford and buried in

Alderbrook Cemetery. The Guilford Free Library holds a collection of his

letters sent to his wife during his brief service in 1862. His descendants

who had settled in Minnesota donated them in 1981 to the Guilford

Keeping Society.

Oliver Evarts was present at battle at Chancellorsville, Virginia when on the

morning of May 3, 1863, the 14th Regiment was located just north and

west of the Chancellor House, where the enemy appeared on their front

and right flank almost simultaneously. Oliver Evarts was killed in action.

African Americans, American Indian and a Horse Thief:

The 1860 census showed that Guilford had a population of 2,624,

including 23 blacks and 26 mulattos.

Twenty-one of the African Americans enlisted in the Civil War to help meet

the town’s quota. One of these, William Henry Wright, who was born in

Guilford traveled to Massachusetts to enlist in the 55th Regiment,

Massachusetts Infantry (Colored) because enlistment in Connecticut had

not yet opened up to African Americans. The monument misrepresents his

unit as the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the unit heralded by the movie

“Glory” in the late 80s.

Three other African Americans who served were married and had families

in town.

Abraham Jackson and Jacob Thompson enlisted in the 29th Regiment,

Connecticut Infantry (Colored), and William H. Porter, upon being drafted,

served in the 11th Regiment, U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.

The other 17 African Americans who helped fill Guilford’s quota enlisted at

the conscript camp in New Haven, serving in the 29th Regiment,

Connecticut Infantry (Colored) and the 30th Regiment, Connecticut

Infantry (Colored). The 30th Regiment failed to organize and was

absorbed into the 31st Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops.

Six of the 21 African American men died during the Civil War, including the

four who are listed on the monument. William Henry Wright died from

tuberculosis and Abraham Jackson from dysentery.

Alexander Peterson and Toby Trout were both wounded at the Battle of

the Crater (Petersburg, Va.) and died at L’Ouverture Hospital (Alexandria,

Va.). Alexander Cunningham, who accidentally shot himself at the

conscript camp in New Haven, and Josiah Cozens, who died while on

furlough, were added to the monument in 2015.

Guilford also had an American Indian who helped fill Guilford’s quota.

Lyman Lawrence, half Pequot, half Narragansett Indian, served in the 29th

CT Infantry (colored) and was wounded at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. He

survived and later moved to Clinton, CT where he operated a laundry

wagon.

And we have Elijah Saunders who stole a team of horses from Guilford.

He was tracked down in New York and brought back to Guilford where he

was offered the option of going to jail or enlist “for” Guilford.

He took the offer to enlist for Guilford, pocketed the bounty money that

came with the enlistment and then deserted shortly thereafter.

111 Goose Lane

Prior to the Civil War, the town played an active role in the Connecticut

Freedom trail. George Bartlett, a strong abolitionist, is reported to have

housed runaway slaves in his cellar here at 111 Goose Lane. His son,

William Nelson Bartlett, nicknamed “Willie” enlisted just after his

eighteenth birthday and fought in several battles.

At the battle at Morton’s Ford, Virginia, the men engaged in hand-to-hand

fighting in the dark. And, throughout the Wilderness campaign, the

regiment fought at five battles, daily losing valuable officers and enlisted

men. During the battle on August 15,1864, at Deep Bottom in Virginia,

Willie was shot through the heart. His body was brought back home and

buried in Alderbrook Cemetery.

829 Goose Lane

George Augustus Foote, Jr., first cousin to Harriet Beecher Stowe, was

among the first of Guilford men to enlist in April 1861, and fought at

the Battle of Bull Run, Virginia before being honorably

discharged in August 1861. He reenlisted a year later, as a Private,

Company I, 14th Regiment, Connecticut Infantry and was promoted to

Sergeant. This house was also the home of Harriet’s mother’s family who

cared for her here after her mother’s death when Harriet was 4 years old.

At the Battle of Antietam, Maryland, when the company became somewhat

disorganized, Captain Bronson called the men to form around “old Foote’s

musket,” which so amused the men that they cheered and quickly formed

again. On the same day, the flag fell and Foote volunteered to carry it for

the rest of the day.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, at Marye’s Heights, the flag

fell again. As Foote stopped to pick it up, he was wounded in the leg and

fell. He was again shot by the Rebels, wounding him slightly in the head

and the hip. He laid on the field the rest of the day; three times the men

charged over him, trampling on his wounded leg. Half delirious, he begged

them to kill him to end his suffering. At night, he managed to crawl off to a

little hut where some other wounded men had hung a yellow flag.

They remained there for three days with little hard tack, and still less water,

when they were discovered by a Rebel officer and a few men who asked

them why they were there. Some of the men said they didn’t want to fight

but were drafted and obliged to. Foote, on the other hand, cooly lifted his

head and said “I came to fight Rebels, and I have found them, and if ever I

get well, I will come back and fight them again.”

“Bully for you,” said the officer, “you are a boy that I like,” and at once gave

him some water out of his own canteen, sent one of his men for some

more water, washed his leg and foot, bound it up as well as he could,

paroled him, and helped him cross the river to the Lacy House, a hospital.

The men gave him a blanket, and even cheered him as the wagon drove

off.

George’s leg was hastily amputated at the Lacy House, and he was moved

to the Armory Square Hospital, where his leg was operated on again and

the bone cut shorter.

His brother went south to tend to him and bring him home. George

recovered some portion of his strength and was offered commission as

2d Lieutenant, but never mustered in, and was discharged as a Sergeant

on July 31, 1863.

After regaining some health he attempted to once again farm, but had to

give that up. He entered the mercantile business for a year, but had to give

that up as well. After a cold brought on conditions of consumption, he went

to Florida hoping to improve his health, but long suffering had shattered his

health, and he gradually declined until his death on November 14, 1869.

605 Nut Plains Road

Joel C. Parmelee was born at and lived in the family ancestral home at 605

Nut Plains Road, Guilford. He was married and had 5 children; four

daughters and a son he named Edward Lincoln.

Joel, age 40, enlisted as a Private in Company C, 27th Regiment,

Connecticut Infantry and was killed in action at the Battle of

Fredericksburg, Maryland, on December 13, 1862. His cousin, Uriah N.

Parmelee lived at 652 Nut Plains Road.

652 Nut Plains Road

A direct descendant of John Parmelee (original planter of Guilford), Uriah

Parmelee, dropped out of Yale College to enlist stating: “what is knowledge

worth to me without a country.” He was promoted for “gallant conduct at

Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.”

While pursuing the Confederates at Five Forks, Virginia, outside of

Petersburg, an enemy regiment was spotted in an orchard.

Thinking the Confederates were unsupported, the 1st Connecticut Cavalry

charged in at a gallop, but as soon as they reached the outer edge of the

woods, the peaceful looking peach orchard assumed a different character;

the bright pink blossoms were blown into the air by bullets, shells, canister

and grapeshot. Every man who had gone into the open field was shot

down. Uriah Nelson Parmelee was instantly killed by a shell to his chest,

just 8 days before the war ended.

Uriah’s words and ideas about slavery, the war, and Civil War politics can

be found in his extensive letters and journals that are used by historians

today to help us understand the war and its soldiers.

959 Nut Plains Road

Brothers George H. Hall and Charles A. Hall along with their brother inlaw,

Joseph Coan, lived at 959 Nut Plains Road. All three enlisted in Co. E,

15th CT Infantry. George was discharged due to disability after serving 6

months. Charles served for almost 3 years.

Their brother inlaw, Joseph Coan, served just 91 days. When Joseph,

while on duty as a company cook became sick with typhoid fever, his twin

brother Jerome, also in the same regiment, was allowed to take care of

him. Jerome remained with him until Joseph’s death on November 7,

1862. Joseph’s remains were sent home and his brother was allowed a

furlough to attend the funeral. Joseph left a wife and 5 yearold

daughter.

In 1860, Guilford had a population of 2,101, occupying 421 households.

These included 23 blacks and 26 mulattos. North Guilford had a total white

population of 523, occupying 111 households.

Between the years 1861 and 1865, the United States was engaged in the

Civil War, the deadliest war in American history. Guilford did its duty,

providing men, supplies and support. The Town sent hundreds of its men

off to the war; sons, fathers, brothers, uncles, cousins and neighbors.

Many of these loved ones did not return and their sacrifices have been

memorialized on the Civil War monument that stands proudly in the center

of the Guilford Green

During the war, Guilford held special town meetings to defend and

maintain the national government “at every hazard and to the last

extremity.” Support and care for the soldiers and their families were

appropriated in town resolutions. Liberty poles were erected in Guilford

and North Guilford. Citizens worked to provide what they could, sending

linens, blankets, mittens, jellies, fruits, pickles and turkeys to their soldiers.

Newspaper subscriptions were sent to the men by members of the Third

Congregational or Abolitionist Church, and a chapel tent was sent to the

soldiers in the 1st Connecticut Light Artillery Battery who had formed a

religious society in their camp. Some of Guilford’s women traveled south

to the camps and battles to tend the wounded and dying and bring about

changes in sanitary conditions.

Even though the majority of citizens supported the war, Guilford had its

share of Copperheads and those who opposed it and wanted a peace

settlement with the Confederates. On August 18, 1861, a Confederate flag

was raised in North Guilford, in exultation over the Federal defeat at Bull

Run. Rebel sympathizers also organized a plan to tar and feather their enemy,

Captain, later General Joseph Hawley, when he visited his wife,

Harriet Ward Foote Hawley’s family in Guilford.

655 Little Meadow Road

George Stevens lived at 655 Little Meadow Road prior to 1860. He

enlisted in the 1st CT Light Artillery before transferring to the Navy.

The Bullard family bought the home around 1860 where Henry B. Bullard

lived with his mother before enlisting in the 1st CT Light Artillery on

October 16, 1861. The men trained at Camp Tyler, West Meriden, Connecticut,

before leaving the state three months later.

Henry Bullard died just 24 days later while on board the Ellwood Walter.

His comrades buried Henry under some giant yellow pines just outside

Beaufort, South Carolina. He was later reinterred in the National Cemetery,

Beaufort, South Carolina. A headstone for him is also located in the Nut

Plains Cemetery. He was the first soldier from Guilford to die.

215 State Street

Samuel H. Hull was injured by a horse falling on him while on drill at

Beaufort, South Carolina. He was discharged from service on April 22, 1863,

after having been ill with chronic diarrhea for over six months. He returned

to Guilford where he died from consumption or Tuberculosis on February 1, 1876.

He is the last soldier to die who is listed on the Soldiers’ Monument.

93 State Street

93 State Street was built in 1865 and used by the Guilford Light Battery,

veterans of the Civil War as a National Guard building until 1885. This

house originally stood at the southwest corner of 89 State Street and

moved to this location in 1903.

48 State Street

Joseph Grosvenor was an apprentice carriage maker who lived with

Samuel Stone, a master carriagemaker. Joseph was one of two Guilford

soldiers who were killed in action at the Battle of Antietam on September

17, 1862. He is buried at the National Cemetery in Sharpsburg, MD.

17 Graves Avenue

Henry Harrison Hall was an apprentice blacksmith who lived here with John

Graves, a master blacksmith. Henry enlisted in Co. A, 10th CT Infantry in

September 1861 and was promoted in December. During the first

regimental battle at Roanoke Island on February 8, 1862, the men

“exhibited great coolness and sterling bravery.” Almost two years later, on

January 1, 1864, Henry reenlisted as a veteran and received a $300

bounty. He was wounded seven months later, on August 14, 1864, at the

Battle of Deep Bottom in Virginia, and died the next day. After his death,

his greatcoat and forage hat were sent to his mother back home.

The research for this tour was compiled by Tracy Tomaselli, a

Guilford historian who is related to four Guilford Civil War Soldiers. She did

extensive work with the National Archives, Genealogy materials and

mid-nineteenth century census data. Thank you to Dennis Culliton for putting

the information into this format.

In 2010, the GPA completed a Survey of Barns and Outbuildings in Guilford, Conn. The survey includes photos and information about 334 barns and outbuildings and was produced in cooperation with the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation. The statewide survey can be viewed online at www.connecticutbarns.org

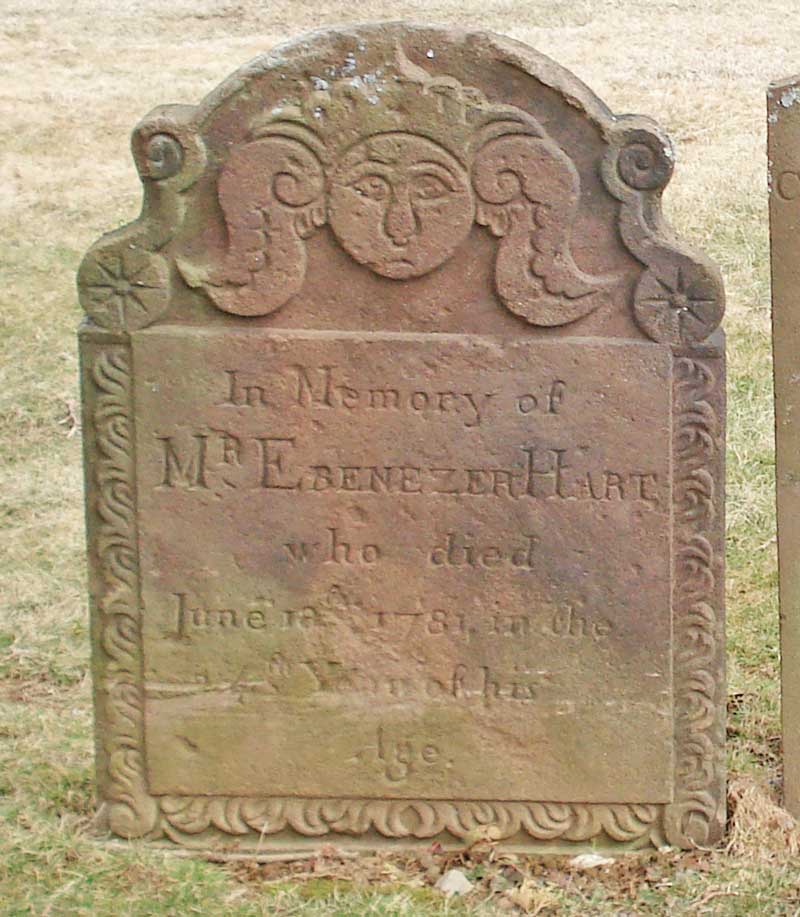

Soon after Guilford’s settlement in 1639, the Town Green became the fledgling community’s burial grounds. Because the Green was also used for other purposes, including militia training and grazing livestock, use of the grounds as a cemetery was eventually deemed inappropriate. In the early 19th century, graves were moved from the Green to two new cemeteries in other parts of town. As Guilford’s population grew in the years that followed, other cemeteries were established including small, private family cemeteries.

Today, Guilford’s cemeteries offer a quiet retreat for visitors to stop at the grave sites of some of Guilford’s notable citizens and to contemplate the stories of their lives.

New information on those laid to rest in Guilford’s cemeteries is continually coming to light through the ongoing research of historians and genealogists. Following are locations of Guilford’s cemeteries and stories of some of those laid to rest in these cemeteries.

The Historical Room at the Guilford Free Library, 67 Park Street, provides many resources that may help including diaries, books, letters, photographs, newspapers, school yearbooks, tax lists and federal census records. For hours of operation and available research assistance, visit www.guilfordfreelibrary.org/historical-room

Established circa 1818, this cemetery is located .8 mile east of the Town Green. Alder Brook is Guilford’s largest cemetery and is the resting place of many of Guilford’s earliest residents. Many of the gravestones were originally located on the Town Green and were moved here in the early 19th century.

Notable burials include:

Fitz-Greene Halleck – Poet

July 8, 1790 – November 19, 1867

Fitz-Greene Halleck’s popularity as a poet reached its zenith in the 1820s and 1830s when he produced “Alnwick Castle” and the long poem “Marco Bozzaris,” considered his masterpiece by his contemporaries.

Born and raised in Guilford, Halleck moved to New York at the age of 20. A banker by trade, he began collaborating with writer Joseph Rodman Drake in a series of satires, “The Croaker Papers,” in 1819. Published anonymously, the series became popular for its irreverent view of New York society and culture. That year, he also published “Fanny,” a satirical narrative poem. The next year, Drake died. Halleck’s grief inspired one of his most famous poems, “On the Death of Joseph Rodman Drake.”

By this time, Halleck’s popularity as a writer drew him into the Knickerbocker group, a circle of New York literati that included Washington Irving and William Cullen Bryant. Though nicknamed “The American Byron,” he continued to work in banking and in other financial jobs.

In 1849, Halleck returned to Guilford and lived here until his death in 1867. In 1877, a statue of Halleck was dedicated in New York’s Central Park by President Rutherford B. Hayes. The memorial’s inscription states: “One of the few, the immortal names that were not born to die.” Halleck is the only American writer honored in the “Literary Walk” of Central Park.

William Graham Sumner – Sociologist

October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910

William Graham Sumner was a sociologist known for his classic work “Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores and Morals,” published in 1906.

Sumner was born October 30, 1840 in Paterson, New Jersey and graduated from Yale University in 1863. He studied abroad in Geneva and Gottingen in the fields of history and divinity and was ordained in the Episcopal Church in 1869. He served briefly as assistant rector of Calvary Church in New York City and then as rector of the Church of the Redeemer in Morristown, New Jersey, from 1870-1872.

On April 17, 1871 he married Jeanne Whittemore Elliott, and they had two sons, Eliot and Graham. From 1872 to 1909 he was professor of political and social science at Yale University, and in 1909 he became president of the American Sociological Society. On December 26, 1909, shortly before he was to address the American Sociological Society at their meeting in New York City, he collapsed. Sumner died on April 12, 1910 and was buried in Guilford in his wife’s family plot, the Elliott Family Circle. The entire family group was later moved to the Alderbrook Cemetery.

________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________

This small private cemetery is the burial site of members of the Foote and Ward family.

Notable burials include:

Roxanna Foote Beecher – Mother of Harriet Beecher Stowe

January 10, 1775 – September 24, 1816

Roxanna Foote Beecher was the wife of Presbyterian minister Lyman Beecher. The Beechers were the parents of nine children including author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Roxanna died when Harriet was only five years old. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s most famous book “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” was published in 1852. The antislavery novel galvanized abolitionists and is cited among the causes of the Civil War.

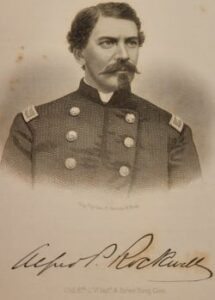

Memorial Stone:

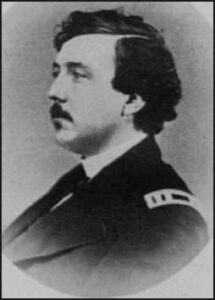

Alfred Perkins Rockwell – Geologist, Educator, Industrialist

October 15, 1834 – December 24, 1903

Although not buried at the Foote-Ward Cemetery, a memorial stone honors Alfred Perkins Rockwell due to his marriage a Foote family member, Katharine Virginia Foote. Rockwell excelled in many areas – as a war hero, a professor, geologist and industrialist. After receiving degrees from Yale and the Sheffield Scientific School in the 1850s, Rockwell started his career in geology by studying at the Museum of Practical Geology in London and at the prestigious Bergakademie at Freiberg, Saxony. He also visited coal mines in Northern England and Germany to study advanced mining technology and the economics of the industry.

At the outset of the Civil War, Rockwell was commissioned as Captain of the 1st Connecticut Light Artillery, earning a promotion to Colonel of the 6th Connecticut Infantry. On March 13, 1865, he was brevetted Brigadier General, US Volunteers, for “gallant and distinguished services in the field during the (Petersburg) campaign of 1864.”

Rockwell served briefly on the Board of Visitors at the U.S. Military Academy followed by stints as professor of mining at the Sheffield School and at MIT. After the fire of 1872 that consumed much of downtown Boston, Rockwell was appointed Chairman of the Board of the Fire Commissioners. He later served as president of the Eastern Railroad and as treasurer of the Great Falls (N.H.) Manufacturing Co., a textile firm. Rockwell wrote two books, Great Fires and Fire Extinction and Roads and Pavements in France. Rockwell died on Dec. 24, 1903 and was interred in the Yantic Cemetery, Norwich, Connecticut.

___________________________________________________________________________________

This small private family cemetery is the burial site of members of the Fowler family.

Notable burials include:

William Ward Fowler – Farmer and Businessman

April 3, 1833 – August 21, 1879

William Ward Fowler was a member of the New Haven County Farmer’s Club and a leading advocate for the cause of intelligent agriculture. He may also have been one of the unluckiest men in the state.

On July 7, 1843, Fowler was sitting on his verandah in the early evening when suddenly a keg of nails rolled from the roof and struck his head, inflicting some 70 cuts and bruises and rendering him unconscious. In October of 1844, after recently recovering from an illness, he dislocated his hip and was confined to his room for several weeks. Previously he had fallen several times and broken bones. Once, while digging a pit for a boulder he came near being crushed. On another occasion, while ascending a stone abutment he fell backward, displacing the bones at one of the hip joints. His barns were destroyed by fires three times and in 1872, his house caught on fire. In 1878, he was confined to his house by typho-malarial fever. On July 25, 1879, while driving between Branford and Guilford, he struck a rock and was thrown from his wagon and dragged about half a mile. Fowler died on August 21, 1879.

__________________________________________________________________________________

This small private family cemetery is the burial site of members of the Goldsmith family. Some members were exiled from Long Island during the American Revolution and moved to Guilford in 1782.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This cemetery was established circa 1801.

Notable memorials include:

Memorial Stone:

Simeon Leete

April 14, 1753 – June 19, 1781

Simeon Leete was shot by the British in a skirmish at Leetes Island near Guilford on June 19, 1781. He was buried on the Town Green. Leete’s tombstone was later removed to the Leetes Island. The pointed rock where Leete was mortally wounded can be found in the front yard at 60 Harbor View Road.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This small private cemetery is the burial site of Rev. William H.H. Murray (“Adirondack Murray”) and his family.

Notable burials include:

Rev. William H. H. Murray – Minister, Author, Outdoorsman

April 26, 1840 – March 3, 1904

“Adirondack” Murray was an orator, outdoorsman, Congregational minister and author of religious and outdoor books including “Adventures in the Wilderness; Camp Life in the Adirondacks” (published in 1869) which popularized the north as a resort and health cure destination. The widely distributed book created the “Murray Rush” of visitors to the Adirondacks. He has been called “The Great Evangelist of Outdoor Life for the People.”

Murray graduated from Yale in 1862 and attended East Windsor Theological Seminary. He served as minister to churches in Greenwich and Washington, Connecticut. In the mid-1860s he became pastor of the First Congregational Church in Meriden, Connecticut and later was pastor of the Park Street Church in Boston. He retired from the clerical profession at the age of 40 and traveled for seven years. The last 12 years of his life were spent on his Guilford homestead.

______________________________________________________________________________

This cemetery was established circa 1818.

Notable burials include:

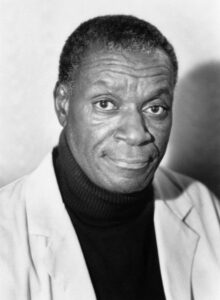

Moses Gunn – Actor

October 2, 1929 – December 16, 1993

Gunn made his debut on Broadway in 1962 and was an Obie Award-winning stage player. He co-founded the Negro Ensemble Company in the 1960s. A veteran a many feature films, some of his most memorable roles were in “Shaft” (1971), “Roller Ball” (1975), “Ragtime’ (1981), “Heartbreak Ridge” (1986), “Bates Hotel” (1987) and “Perfect Harmony” (1991). He was nominated for an Emmy Award in 1977 for his role in the TV mini-series “Roots.” Television credits include “Kung Fu,” “Little House on the Prairie,” “Good Times,” “Father Murphy” and “Homicide: Life on the Street.”

____________________________________________________________________________

Located in picturesque North Guilford, this cemetery contains the graves of several American Revolutionary War patriots. Also located here is the grave of Shem, an African American slave owned by Rev. Joseph Elliot. (GPS Coordinates: Latitude: 41.22044, Longitude: -72.43682)

____________________________________________________________________________________

Located north of the Town Green, this Catholic cemetery was established circa 1885.

_________________________________________________________________________________

This cemetery was established circa 1818.

Notable burials include:

Edward Merwin Lee – Civil War General

August 23, 1835 – January 1, 1913

Lee was a served as Lieutenant Colonel of the 5th Michigan Volunteer Cavalry, which was a part of the famed “Michigan Wolverine” brigade commanded by General George A. Custer. He was brevetted Brigadier General, US Volunteers on March 13, 1865, for “gallant and meritorious services during the war.”

_________________________________________________________________________________

Guilford’s “Little Augusta” is an Executive 9-hole golf course. For more information please go to the Guilford Lakes Golf Course website at: https://www.guilfordlakesgolf.com

Guilford is an agricultural community. There are currently about 40 farms operating in our small town. Residents and visitors can also take advantage of two Farmers Markets to purchase locally grown, fruit, vegetables, and homemade goods. The Dudley Farm Farmer’s Market operates in North Guilford on Saturday mornings and the Farmer’s Market at the Fairgrounds operates on Thursday evenings.

![]()

Jacobs Beach

Chaffinch Island

Nut Plains Park

Daniel Avenue Beach

Rollwood Park

Chittenden Park

Bittner Park

Lake Quonnipaug

Women’s Boutique carrying handcrafted jewelry, belt buckles, clothing, accessories, and gift items. Many unique one-of-a-kind finds.

September 17-24, 2023, on and around the Guilford green. The festival is back with a brand new name and better than ever! Twenty-five free live performances and family-friendly events including storytelling, folk, jazz, classical and world music. Ballet and contemporary dance. Music, dance and stories of Puerto Rico, Ukraine, Egypt and India. Puppet shows, circus skills, plein art painting, stand-up comedy. A DIY StoryCorps booth where you can tell your story! Be there, on and around the Guilford Green! For more information and the schedule of events, visit www.greenstageguilford.org.

Located on the historic Guilford Green, Tracy Brent Collections & Tracy 2 offer clothing and accessories for the sophisticated woman looking for that unique outfit or finishing touch. Find some of the best designers of the world, right here in Connecticut. Our style experts at Tracy Brent Collections will help you create the perfect look for any occasion. Our diverse selection of clothing, jewelry, bags and other accessories makes us the perfect stop for your fashion needs. Love your style at Tracy Brent Collections & Tracy 2.

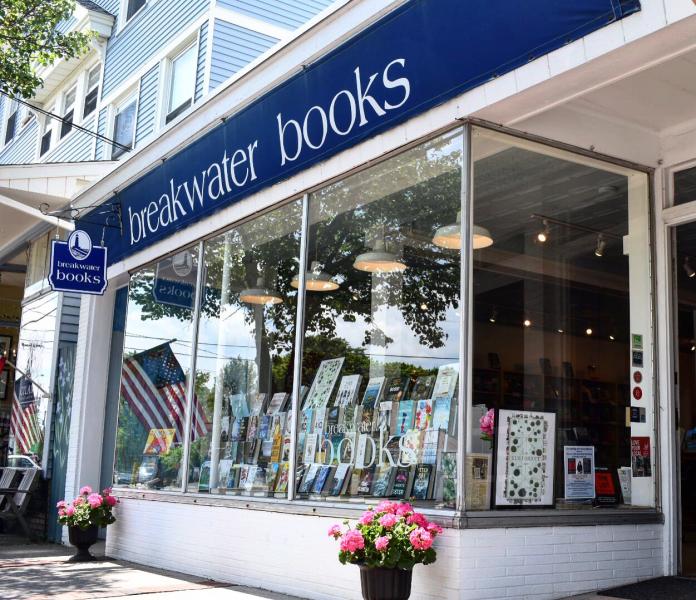

Breakwater Books is an independent bookstore located on the historic Guilford Green. We carry adult, YA and children’s books as well as cards, puzzles, games and gifts for book lovers. We have been serving the Guilford community since 1972 and we would love to meet you.

View our website: https://www.breakwaterbooks.net

The Guilford Poets Guild was organized in 1998, and in 1999 the organization produced “An Anthology of Guilford Poets.” The Guilford-area poets meet regularly to discuss poetry, plan readings, and work with high school students in local schools. In 2009 the group published “The Guilford Poets Guild Tenth Anniversary Anthology.”

Fitz-Greene Halleck – Poet

July 8, 1790 – November 19, 1867

Fitz-Greene Halleck’s popularity as a poet reached its zenith in the 1820s and 1830s when he produced “Alnwick Castle” and the long poem “Marco Bozzaris,” considered his masterpiece by his contemporaries.

Born and raised in Guilford, Halleck moved to New York at the age of 20. A banker by trade, he began collaborating with writer Joseph Rodman Drake in a series of satires, “The Croaker Papers,” in 1819. Published anonymously, the series became popular for its irreverent view of New York society and culture. That year, he also published “Fanny,” a satirical narrative poem. The next year, Drake died. Halleck’s grief inspired one of his most famous poems, “On the Death of Joseph Rodman Drake.”

By this time, Halleck’s popularity as a writer drew him into the Knickerbocker group, a circle of New York literati that included Washington Irving and William Cullen Bryant. Though nicknamed “The American Byron,” he continued to work in banking and in other financial jobs.

In 1849, Halleck returned to Guilford and lived here until his death in 1867. In 1877, a statue of Halleck was dedicated in New York’s Central Park by President Rutherford B. Hayes. The memorial’s inscription states: “One of the few, the immortal names that were not born to die.” Halleck is the only American writer honored in the “Literary Walk” of Central Park.

The Guilford Art Center is a non-profit school, shop, and gallery established to nurture and support excellence in the arts. Through classes for adults and children, gallery programs, a shop of contemporary crafts, and special events, the Center fulfills its mission to provide opportunities for the public to participate in the arts, to experience their cultural and historical diversity, and to appreciate the process and product of creative work. The Center seeks to preserve craft traditions and foster innovation by providing an environment where artists can gather, practice, exhibit, teach and exchange ideas.

Founded in 1967 (as the Guilford Handcraft Center), the Center evolved from the first Handcraft Expo, held on the Guilford Green in 1957, in which local artisans displayed and demonstrated their crafts. Ten years later, the Center was incorporated and, since that time, has become a vital part of the town and the shoreline community and culture. It serves as the most comprehensive art organization, and includes the largest public exhibition space, between New Haven and Old Lyme.

The school annually serves over 2,000 students, from preschool-aged through senior citizens, in four semesters of approximately 350 classes, including ceramics, jewelry, metalsmithing, weaving, glass, drawing and painting, blacksmithing and stone carving. Tuition assistance is available to help insure that the Center’s programs are accessible for community members of all means.

The Center’s gallery presents juried and invitational exhibits of art in all media and is open seven days a week, free of charge. The Shop, open year-round, features fine, handmade American crafts; an annual highlight is the Artistry Holiday Sale of Fine American Craft, which includes works by more than 300 artisans. Craft Expo, held on the Guilford Green each July, features works by more than 180 of the country’s most distinguished artisans and is a much-anticipated annual event for the shoreline community.

Check our website for upcoming classes, programs, and events: http://guilfordartcenter.org

The Guilford Art Center is handicap accessible.

Directions:

I-95 to Exit 58; north on Route 77 for 200 yards.

Guilford Art Center is on your right, just past the blinking light.

CTSA is an informal group of painters who like to paint outdoors in the landscape.

It was founded in 2007 by a few people who had met in outdoor watercolor classes at the Guilford Art Center; as it became more established, the group took the name Connecticut Shoreline Artists (CTSA) in 2010. It is based in Guilford but includes painters from along the Connecticut shoreline. Depending on weather, every week from around mid-April to early December participants (with their gear for watercolor, pastel, oil, or acrylic painting) arrive on Thursday morning at a location somewhere between the Branford River and the Connecticut River. Numbers can include anything from two to two dozen painters, or more. All media, all ability levels, all welcome!

A volunteer from the group arranges the venues and provides information about the location plus driving directions, posted on the CTSA Blog. After each session, a brief summary with photos of the place and some of the paintings is usually posted on the blog. Painters often stay on for lunch, outdoors or at a local cafe, to chat and to share information about art activities in the area. From time to time, there are opportunities to show paintings at a local museum or other venue.

CTSA has no dues, no formal membership, no by-laws, no participation requirements, and no officers. It exists purely to provide a time and place for plein air painters to paint together on the beautiful shoreline and rural countryside in and around Guilford.

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: https://guilfordlandtrust.org/wordpress/

Printed maps are available at:

Photo credit: Guilford Conservation Land Trust

For information and trail map please go to: Timberland Preserve

Passive recreation only. Limited number of trails which are multipurpose.

For fishing regulations and licenses please go to: https://portal.ct.gov/DEEP/Fishing/CT-Fishing

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: https://guilfordlandtrust.org/wordpress/

Photo credit: Guilford Conservation Land Trust

Access permits are required. Please contact the Water Authority https://www.rwater.com/in-the-community/recreation.

Trail map: https://web1.myvscloud.com/images/ctsouthcwa/splash/areas/Sugarloaf.pdf

Sugarloaf’s gated entrance and parking area is located on West Street. Take Foxon Road/North Branford Road (Route 80) to Country Road (aka West Street) near the North Branford town line to the left fork to West Street.

A Regional Water Authority (RWA) Recreation Area – this scenic recreation area got its name many years ago because its two rounded hills resembled mounded loaves of brown sugar. Today, West Sugarloaf is covered with plantations of white pine and Norway spruce and has become a roosting area for wild turkeys.

The Owl Trail has many old rotting tree trunks which are homes for many small forest animals such as screech owls and chipmunks. Look carefully and you may find an owl sleeping in the crook of an old tree.

The Sherwood Forest Trail has sugar maples that provide such a dense cover during the summer that little under-story grows here. As you walk along, you may be able to see up to 500 feet through the forest in this enchanted area. There is a long, steep climb on this trail as it ascends the west side of Sugarloaf.

Raven’s Trail is a short, steep trail that climbs over the top of the east Sugarloaf and provides a shortcut on the east leg of the Owl Trail.

The Tangled Web Trail is named for the overgrown tangle of grape vines, briars and berries growing over a section of the west Sugarloaf hill. It is an especially good place for bird watching. Merlin’s Way is a short trail that connects the Sherwood Forest Trail to the Tangled Web Trail.

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: https://guilfordlandtrust.org/wordpress/

Photo credit: Guilford Conservation Land Trust

Parking is available at Cox School (.25 miles north of the site).

(Audubon Connecticut)

Guilford Salt Meadows Sanctuary is located along the East River, a tidal river that drains into Long Island Sound. The tidal wetlands that form the heart of the Guilford Salt Meadows Sanctuary are a remnant of the great salt and brackish water marshes that once extended nearly continuously along the Atlantic Coast from Maine to Georgia. These wetlands support specialized saltmarsh vegetation and animal life. They also provide vital refueling and nesting stops for thousands of migratory birds.

The sanctuary can be viewed from the Anne Conover Nature Education Trail, a one-mile loop that is an easy walk for people of all ages. The sanctuary’s nature trail is open to the public daily from dusk to dawn.

Trail map: guilford.audubon.org/PDF/AnneConoverNatureEducationTrailMap.pdf

For information, trail maps, and directions please go to the Guilford Conservation Land Trust website at: https://guilfordlandtrust.org/wordpress/

Photo credit: Guilford Conservation Land Trust