THE MENUNKATUCK— GUILFORD’S INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ HERITAGE

Quinnipiac society was organized under a grand sachem, or paramount leader. That leader’s sachemdom, or territory, was comprised of several smaller regions presided over by secondary leaders, also called sachems. More than a dozen of these smaller sachemdoms, including the Menunkatuck band at Guilford, lay within the Quinnipiac sphere of influence.

A century of European exploration and trade in the Americas introduced unfamiliar microorganisms into New England prior to the settlement of colonies in the region. Smallpox, plague, and other diseases claimed as much as 80% to 90% of the indigenous population. This death toll shattered Indigenous peoples societies, rending socio-political structures and upsetting delicate balances among allies and enemies. This devastation set the context encountered by the Puritans when they came to “civilize” the New World.

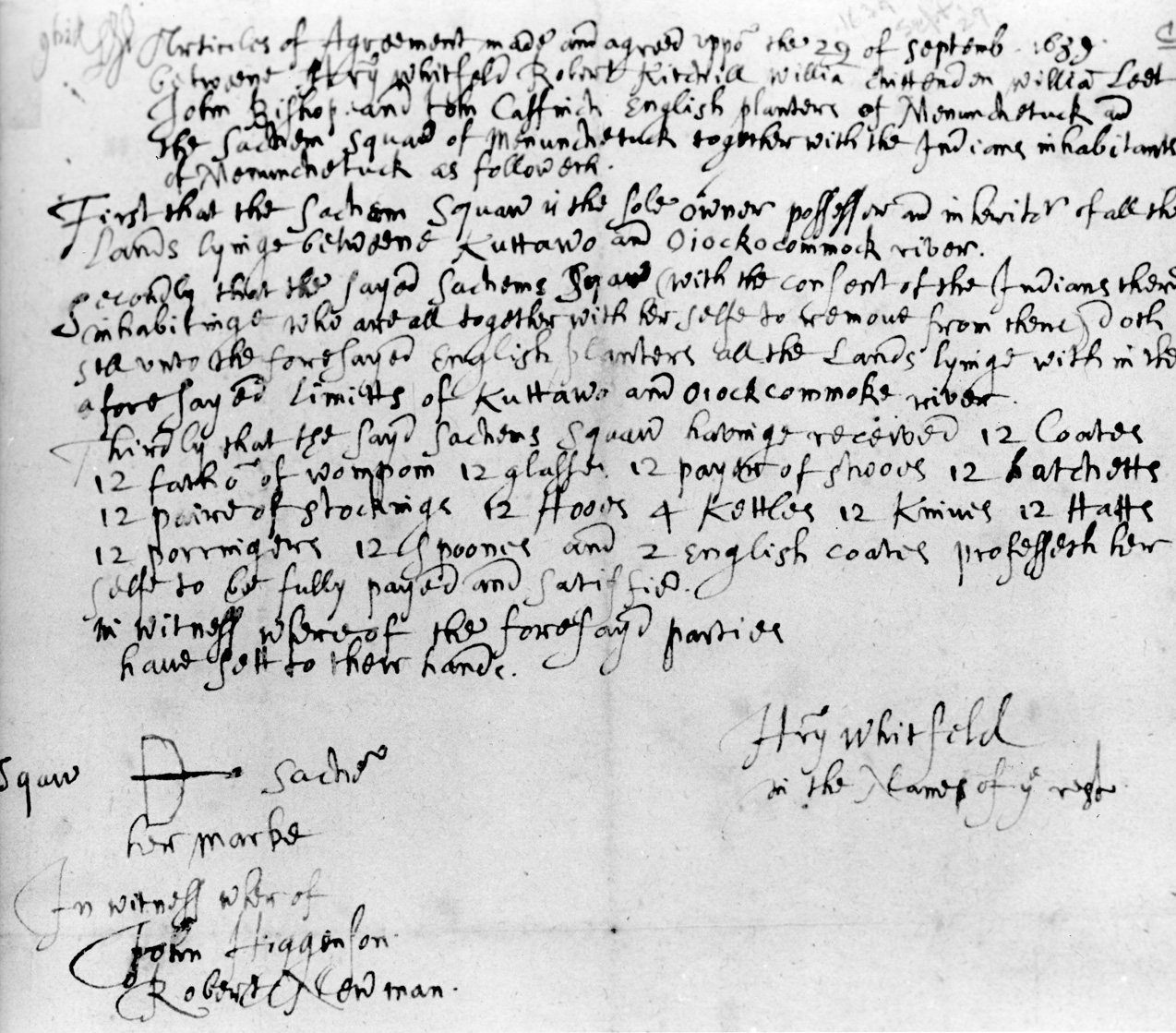

In 1639, the land that would become the Plantation of Menunkatuck was home to the Menunkatuck band, whose name may refer to the fertilizer generated by the abundant menhaden, a fish in the herring family. The Menunkatuck were led by a female sachem, often referred to as the Squaw Sachem, Shaumpishuh. She was sister to the Grand Sachem Momaugin, who signed the First Treaty with the English planters at New Haven in 1638. In 1639, Shaumpishuh signed a deed that conveyed use of all the land of present-day Guilford with the exception of North Guilford, but reserving land east of the Kuttawoo River (the East River). This deed was drafted by William Leete and based on a map created by Shaumpishuh and her uncle, Quosoquonch, sachem to the nearby Totoket band. The map is dated August 23, 1639, and the agreement was signed on September 29th of that year.

The price paid to Shaumpishuh by Guilford’s founding fathers included “12 coates, 12 fathom of Wompom, 12 glasses, 12 payer of shooes, 12 Hatchetts, 12 paire of stockings, 12 Hooes, 4 kettles, 12 knives, 12 hatts, 12 poringers, 12 spoons, and 2 English coates” (Steiner, History of the Plantation of Menunkatuck, 1897). For a leader whose people had been beset by war with the Pequots and Mohawks and who had suffered an epidemic in the early 1630s, these goods may have been crucial for survival. The Menunkatuck honored the agreement, removing themselves from what would become Guilford and settling east of the Kuttawoo.

Expanding colonial settlements, involvement in Great Britain’s wars, and changing attitudes among the Puritan leaders led to further decline of the indigenous population. The last Quinnipiac land in the region was in colonial hands before the start of the American Revolution. However, as late as the 1840s, some Quinnipiac descendants would return to fish, clam, and sell baskets along Connecticut’s East Shore. In the present, as many as 200 families may trace their lineage to the Quinnipiac of Connecticut.

Today, place names on the landscape still evoke memories of Indigenous peoples’ heritage in Guilford… Sachem’s Head—the site of a battle with the Pequots; Uncas Point—named for a Mohegan sachem; Old Kuttawoo—the Menunkatuck name for East River; and even Connecticut—a Mohegan word, Quinnehtukqut, that means “beside the long tidal river.”

From the Collections of the Mass. Historical Society, courtesy of J. Helander